Crawling their Way into Science… and all Worm Biologists’ Hearts

RUSHALI

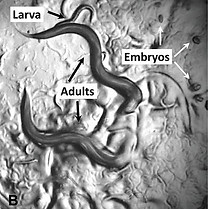

Every PhD student develops some connection or bond with something they work excessively with in their lab; after all, you are spending almost 5-7 years understanding them, analysing them, and possibly even having a love-hate relationship with them! My journey was the same, and my connection was with a model organism. I work on decoding the cellular mechanisms that occur with aging and stress and I use Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny worm, to do this. They are fascinating creatures used as development or aging models, and four Nobel prizes have been awarded for studies that used this worm (2002, 2006, 2008, 2024). They are transparent and can be imaged easily, have a short life cycle and lifespan, and share about 30% homology with us. These have crawled their way all across the soils of science.

Fig: Advantages of carrying out research on the worms

Photo credits: WormAtlas

Courtesy of WormBook.org and used by permission.

Fig: Pile of worms on NGM plates,

courtesy of WormBook.org and used by permission.

Before I joined the lab, I found all these aspects really interesting. I was excited to work with them. When I was first shown the worms under the microscope, they were so fun to watch. They would be crawling around in a huge population, moving on top of or bumping into each other, sometimes rising up above the agar surface as though they were greeting the observer. I stared at them for hours, took a million pictures and videos of them and could not stop showing off.

Illustration by Rushali

Then came the drudgery of PhD work. I had to study the cellular pathways of these worms, memorize the names of their neurons, organs, understand what had been done in the field of worm biology before, and what were the recent advances happening in the field. I had to understand how genes could be modified and what their roles were in worm biology. I started getting bored and uninterested. Their novelty wore off, and I found myself hating them. I found them unrelatable and felt the work I would do with them would be of no use to society. This was the part of my PhD which required study and reading and I was already drained. What would I be contributing to science using them?

Then came the experiment design and performing the experiments. I saw all that boring reading coming to life in front of my eyes. I found genetics and genetic crosses a dry topic, however, while crossing the worms, I saw phenotypes following Mendelian rules in front of me! I could see heterozygous progeny, I could see the elimination of undesirable traits just by the worms mating. I could see pleiotropy in their population. No two worms are the same despite being from the same parent. The theories that I had learned started came alive as a reality in these experiments.

Fig: Theories translating to practicals in front of my eyes when I performed experiments

Illustration by Rushali

Illustration by Ipshita

In the process of doing experiments with the worms, I also found myself empathizing with them. I felt bad if I accidentally killed them (Am I a mean God of some sorts?), dropped a plate full of them in the dustbin (I felt like I was the meteorite that wiped them off) or interrupted their mating process (why was I ruining their lovey-dovey time?). Sometimes, if I performed experiments on them like prodding them with the worm-pick to check if they were alive, I imagined them cussing at me.

Illustration by Ipshita

Mice and rat models require dedication and constant effort, cell cultures require complete sterility and discipline, other models also require a great deal of effort to maintain and work with, while the worms, even when we have fished their plates out of the dustbin at times when we accidentally throw them, thrive happily no matter what.

As my experiments progressed, I started working with worms with certain proteins tagged with the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). I could observe their internal tissues, fluids, and cells in dynamic motion. It looked like magic, like a mini-universe contained inside the microscopic organism. That was the moment, I think, I accepted them wholly.

Fig: Fluorescent worms where I can see their muscles, neurons and intestines

Illustration by Rushali

My initial hate towards them disappeared with my progress in this field. The drabness of the field now became an area of unexplored knowledge and with time, I found myself respecting the value of the organism. I felt grateful for their simplicity and the ease of working with them, and how worm biologists across the world and I, use this tiny worm model to understand our cellular workings and ourselves better.

The relationship that I have with this organism is far beyond work and research.

I connect with them with gratitude and care. While working with them does not require ethical clearance, I would always feel bad if any experiment required killing them. I enjoy working with them because understanding core processes like how ageing occurs, and how keeping them on

a restricted diet extends their lifespan, how with age their inner workings also slow down, etc. is like gaining insight into myself.

For a person who started out wondering why and what the point was to work with worms, I am now proud to say that I am a worm scientist (I do get a lot of laughs for saying that)."

"

RUSHALI

About Rushali

Rushali Kamath is a third-year PhD scholar at IIT Mandi. She loves her research which could be frustrating at times, working with worms and doodling in her free time. She adores travelling all across Himachal in her free time and experiencing nature.

Related Posts

From a Cell’s Perspective

PRABHLEEN

"My organisms are human cells that grow and divide. These babies are actually grown outside the human body in specialised dishes. They need their customised food for energy, a nice warm and humid environment, and like any child, they need enough space to play and grow. They also need other cells as their friends to connect with!"

Share this page: